Last week I attended the Ontario Library Association’s Superconference. It marked my third and last year on OLITA Council. OLITA is the Ontario Library Information Technology Association and it was an honour and a pleasure to serve as a part of it.

I mention this fact to give context to the following scenario. On Thursday morning of the conference, I was sitting in the Toronto Metro Conference Centre, listening to the keynote by Robyn Dolittle and how she described how she had uncovered terrible systematic problems in the police investigation of rape in Canada through her investigative reporting series called Unfounded. Because of her work and because she made academic research on the matter of rape more widely known, police forces across the country have reformed how they keep track of sexual assault statistics and some have taken steps to provide better training of their officers.

After her talk, I opened my phone which brought to my attention that, back in Windsor, there were several social media posts from two members of a local, government-funded technology business incubator who were complaining that the people were sharing the results of a recent research report about the poor economic status of women working in IT in Windsor, and by doing so they “were telegraphing negativity” , “were making things worse”, and “were part of the problem“.

The report in question is called Who are Canada’s Tech Workers and it was prepared by the Brookfield Institute using data from Statistics Canada.

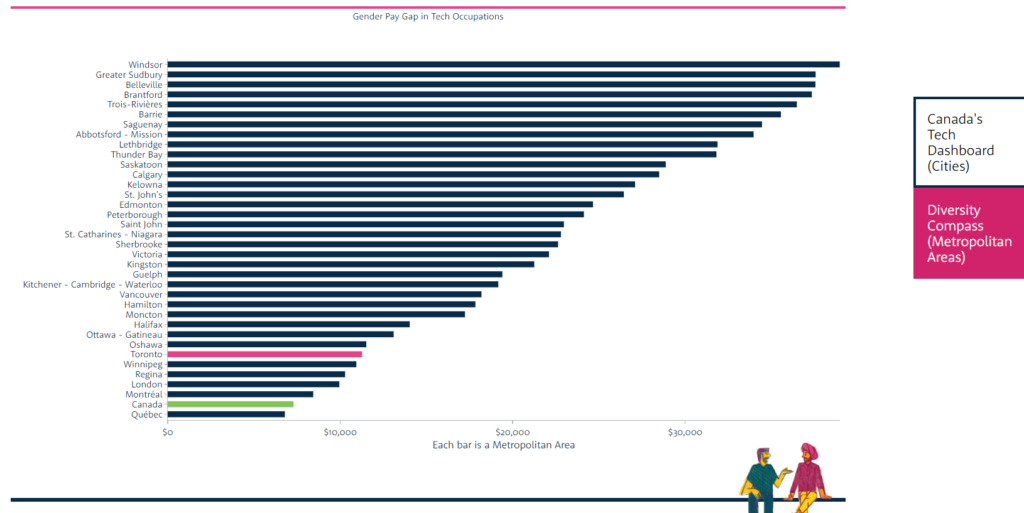

The pay gap for women working tech jobs in Windsor is the highest in Canada’s metropolitan areas, according to a report prepared by the Brookfield Institute using data from Statistics Canada. The report said the average female tech worker in Windsor makes around $39,000 less — or 58 per cent — than what the average male makes.

“Windsor has Canada’s largest pay gap for women in jobs using tech skills: report“, Chris Ensing · CBC News · Posted: Jan 30, 2019

Windsor’s data can be found through the Brookfield Institute’s Canada’s Tech Dashboard (Cities) using the Diversity Compass filter:

I’m not going to extensively comment on these reactions to the reactions to this research because, frankly, I find them absurd. When you find evidence that a practice or a policy isn’t working, the solution is not to bury the research or the reporting of that evidence.

I believe in the power of investigative reporting to raise issues, to generate protest, to encourage the public to ask difficult questions, and to lead to the political and grassroots organizational work that is necessary to make change.

I believe in the power of the work of Robyn Dolittle. I believe in the power of the work of Tayna Talaga. I believe in the power of the work of Kate McInturff who produced four years of the Making Women Count report before she died of cancer in 2018.

It is not possible for me to re-create Kate McInturff’s index of the best and worst cities in Canada for women. But I am going to try to see if I can find the data that might show if things have improved in our city since her last report in 2017.

The Making Women Count report was a comparison of how men and women are faring in five areas: economic security, leadership, health, personal security, and education. I have already covered personal security. With the release of the Brookfield report, it is a good as time as ever to check in with our state of economic security.

Economic Security

The score for economic security is calculated based on four indicators: employment rate, full-time employment, median employment income, and poverty rate, measured as the percentage living below the low-income measure after-tax (LIM-AT). Scores are calculated based on the female-to-male ratio for employment and incomes and the male-to-female ratio for poverty rates. The sources of the statistics are the Labour Force Survey and the Canadian Income Survey (for the poverty measure)

The Best and Worst Places to be a Woman in Canada 2017, p. 83 [pdf]

In doing this series I’ve learned that while there are many Statistics Canada reports that have some account of gender, these reports are generally at the national or provincial level. There are not many at the CMA (Census Metropolitan Area) or city level. It took great deal of labour to generate the city-level statistical tables behind the Making Women Count indexes.

Case in point: Melissa Moyser of Statistics Canada produced this very useful chapter entitled Women and Paid Work from the larger Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report. But the reporting is not focused at the differences between cities. And on the other hand, there are reports from Stats Canada that look at various labour market indicators for the CMA of Windsor, but this data isn’t readily parsed by gender.

However, there is someone in the community who has parsed the local Statistics Canada data from the Windsor both thoroughly and critically, and that person is Frazier Fathers. The following is an excerpt from his most recent post entitled On Tech Wages, YQG Perception and Leadership from his blog, Ginger Politics:

These are facts from the 2016 Census for the Windsor CMA (the same geography and base data as the Brookfield’s Report):

3,710 women (compared to 2,405 men) live in our region and speak neither English nor French. – Creating barriers to accessing education, employment or services.

Median income for women after tax $27,050 (vs $40,881 for men); average $31,364 ($44,208) – they make less money.

Female income percentage from employment: 64% vs 72.6% for men – women are more dependent on government transfers for income than men. There is some qualification bias here.

81% of lone parent families are led by women. – single women are raising more kids then men.

After tax 7,300 women over the age of 15 have 0 total income (5,860 men)

52% of women live in the bottom half of the income distribution vs 48% of men.

30,120 women and girls are living in low income (LIM-AT) compared to 26,635 men and boys.

Workforce participation rate for women in the census was 56.1% compared to 64% for men.

“On Tech Wages, YQG Perception and Leadership“, Frazier Fathers, Ginger Politics, January 31, 2019

I also appreciate that Frazier called out of Yvonne Pillon’s undermining the results of the Who are Canada’s Tech Workers report and of the Making Women Count series by challenging the methodology of both the Brooking Institute report and the CCPA reports, without providing any reason why.

This whole matter is not a surprise to me. It reminds of this quotation:

When you expose a problem you pose a problem. I have been thinking more about the problem of how you become the problem because you notice a problem. When exposing a problem is to become a problem then the problem you expose is not revealed. For example, when you make an observation in public that all the speakers for an event are all white men, or all but one, or all the citations in an academic paper are to all white men, or all but a few, these observations are often treated as the problem with how you are perceiving things (you must be perceiving things!) A rebuttal often follows that does not take the form of contradiction but rather explanation or justification…

The Problem of Perception, feministkilljoy, February 17, 2014

This has happened to me. Two years ago I wrote a piece called Building a culture of critique that explained why I thought WETech Alliance’s Nerd Olympics was an activity that research has shown to turn women and other underrepresented groups away from STEM. The response I received from WETech Alliance was that I did not really understand the situation. I was told my perception was wrong.

Let us not forget that each data point in Statistics Canada is a person. The data made available to us from Statistics Canada shows us that the technology companies in Windsor are under-paying the women they employ. These women are real. They are being underpaid. It is not a problem of their perception.

The purpose of presenting local data is that it brings insight down to a level of a governance where we, the community, are able to make meaningful change. The fact that many cities in Canada do a much better job than Windsor in regards to how women fare suggests that we have the opportunity to learn and adopt the evidence-based policies and practices that they have employed. That is, we can do this if choose to read and learn from the research, rather than dismiss it.

I cannot see myself working with an organization whose president and employees publicly state that if I raise a matter of injustice related to sexism (or racism, class, or ableism for that matter) that I am “part of the problem”.