Some years ago – I think it was 2015 – a friend of mine kindly gifted me the game Mini-Metro on Steam because he guessed that I would love it. He was right.

Mini Metro is a strategy simulation game about designing a subway map for a growing city. Draw lines between stations and start your trains running. As new stations open, redraw your lines to keep them efficient. Decide where to use your limited resources. How long can you keep the city moving

Mini-Metro on Steam (currently 50% off!)

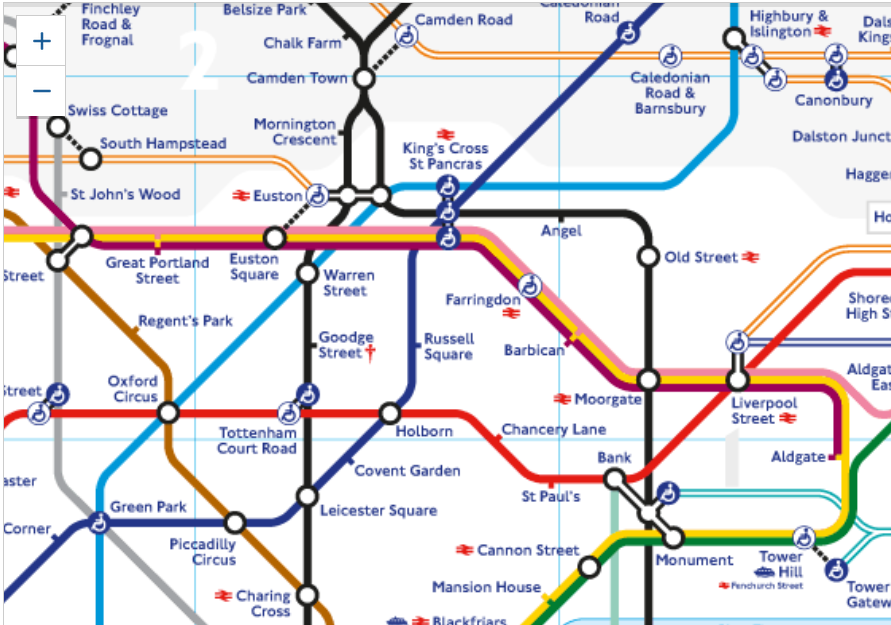

I love the clean and elegant design of the game. The game brilliantly uses the form of the London Underground Map as the vehicle for an abstract puzzle strategy game and so the game feels meaningful, even through the game-play is primarily connecting lines to nodes. But despite my affection for Mini-Metro I don’t play it very much largely because I’m not particularly good at this game.

But recently I got to reading a book that not only helped me better understand how public transit works, it gave me the reason why my Mini-Metro game was so bad. The book is called Human Transit: How clearer thinking about public transit can enrich our communities and our lives.

I picked it up largely because of this recommendation from Tom MacWright:

Easily the best book I’ve read related to transportation. Human Transit doesn’t just describe transit systems – it puts you in the position of a planner and makes you think about the inherent tradeoffs to different designs. It’s rich with good examples from around the world and has an incredible focus – Walker wastes little time on extended biographies or anecdotes.

The balance between different modes of transit is accomplished extremely well, and it also doesn’t focus solely on super-dense cities, but takes into account varying density, suburbs, and how much density is necessary to build great transit, if at all.

I really enjoyed this read, and would recommend it to anyone interested in transportation…

I read Human Transit by Jarrett Walker on July 7, 2018 by Tom McWright

I haven’t finished it yet but I share Tom’s enthusiasm for the book. It is one of the best examples that I know of an expert who can walk a layperson through a series of understandable concepts without ever sounding preachy or condescending. By the way, students and staff of the University of Windsor have access to Human Transit as an ebook.

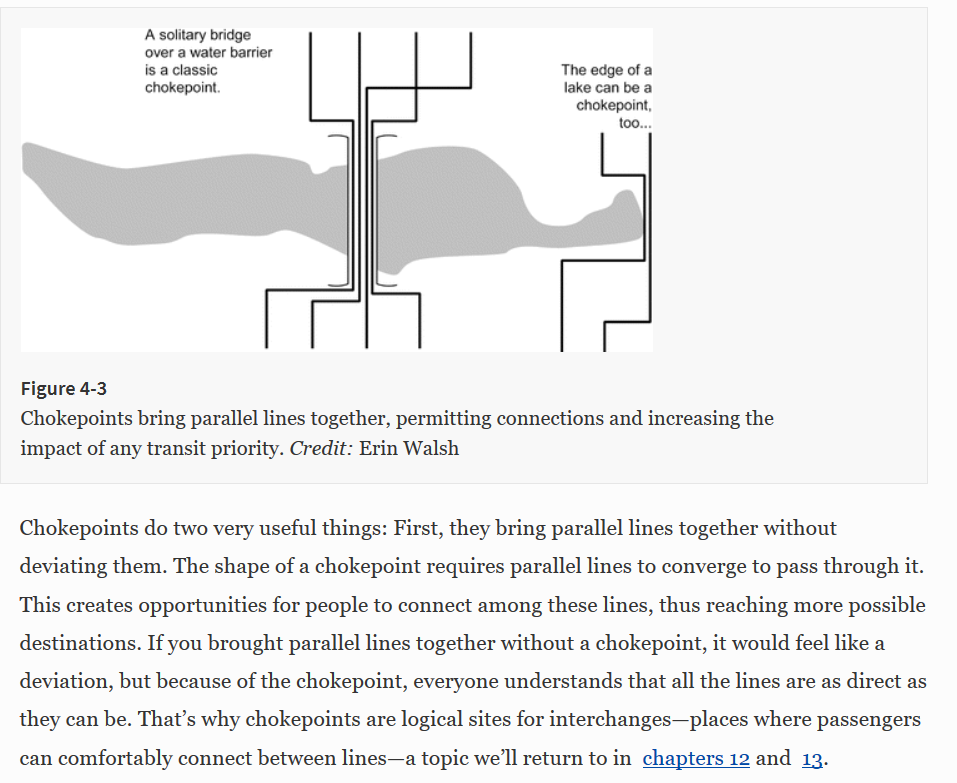

At the moment, I’m on Chapter 4 which is titled, “Lines, Loops, and Longing” and I’m learning so much. For example, I had never realized that “For car traffic, chokepoints are a problem, but for transit, they are opportunities”:

I also learned that the reason why my strategy for Mini-Metro was not good: I was falling into the natural tendency to create loops to connect my ‘stations’.

When someone wants all parts of an area to be connected, and tries to express this in the language of transit, they often talk about loops. The loop is an appealing image because it’s a thing that transit can do that seems to encompass an entire two-dimensional area with a feeling of completeness and closure. I have lost count of how many times people have explained their mobility needs to me by saying, “We need some kind of loop.”

But there’s a problem with loops, and it’s so obvious that it’s easy to forget: very few people want to travel in circles. Most people experience their travel desires as “I am here and I need to be there.” The desire for transportation is a feeling about two points of space, “here”and “there.” In the geometry of cities, the shape of that desire is a straight line connecting those points.

Walker J. (2012) Lines, Loops, and Longing. In: Human Transit. Island Press, Washington, DC

And this was the passage that made me want to play Mini-Metro again, but this time armed with transport knowledge:

Loops have other problems. An I-shaped line can easily be extended on either end without affecting the existing riders, but loops can’t be extended; a city that outgrows its loop has to break it apart, disrupting existing trips. So if an urban area is growing or changing, loops may limit the options for growth in the future.

Finally, of course, loops run with a driver raise the problem of driver breaks. An I-shaped or U-shaped line has an endpoint where the vehicle is empty, so the driver can take a break without disrupting any passenger’s trip. These breaks also serve a second purpose: when a service runs late, the break is shortened so that the vehicle can get back on time. Providing these breaks is a great logistical challenge on busy loops, like the circular rail lines in Berlin, Moscow, and Tokyo. In 2009, the London Underground broke apart its Circle Line, which used to run as a continuous loop, partly to eliminate these problems.

Walker J. (2012) Lines, Loops, and Longing. In: Human Transit. Island Press, Washington, DC

Speaking of games, as I was searching around Jarrett Walker’s blog, I was delighted to read a post in which Walker describes how he helped TransLink in Vancouver BC use a geographical planning game to build stakeholder consensus around a transit plan.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the More than Transit survey from Transit Windsor is ending on January 9, 2019. If you would like to learn more about the possibilities of significant expansion for Transit Windsor in the near future, I’d recommend a listen to this episode of Rose City Politics. And of course, I highly recommend a read of Human Transit. I will end this post with a quotation from the Introduction of Walker’s book – with a couple of links that I have added for related reading:

When someone asks me what I do, and I say I’m a transit planner, their next question is almost always about technology. They ask my opinion about a rail transit proposal that’s currently in the news, or ask me what I think about light rail, or monorails, or jitneys. They assume, like many journalists, that the choice of technology is the most important transit planning decision.

Technology choices do matter, but the fundamental geometry of transit is exactly the same for buses, trains, and ferries. If you jump too quickly to the technology choice question but get the geometry wrong, you’ll end up with a useless service no matter how attractive its technology is.

What’s more, the most basic features that determine whether transit can serve us well are not technology distinctions. Speed and reliability, for example, are mostly about what can get in the way of a transit service. Both buses and rail vehicles can be fast and reliable if they have an exclusive lane or track. Both can also be slow and unreliable if you put them in a congested lane with other traffic. Technology choice, by itself, rarely guarantees a successful service, and many of the most crucial choices are not about technology at all.

Walker J. (2012) Introduction. In: Human Transit. Island Press, Washington, DC